The Most Unique Advantage Play Ever?

Michael Larson.

When I think of someone who had the brains to do a lot more with his life than he accomplished, Michael Larson is one of the first people that springs to mind.

Granted, many people are capable of pattern-recognition, in fact, it is that very same pattern recognition that leads to the “Gambler’s Fallacy,” for many an unfortunate system advocating soul. There are rare occasions, however, in which pattern recognition can be turned to someone’s favor.

For those advocates of, “Visual Ballistics,” in Roulette, that skill, such that it exists, essentially comes down to pattern recognition. The notion is that they look at the ivory ball spinning around the wheel and, after observing the wheel for a time, start to see patterns in how the ball behaves as close to when the croupier calls off any further bets as possible. Theoretically, the Visual Ballistician (if I may) would prefer a croupier to wait until the ball has almost begun a steady descent before calling out, “No more bets,” and that gives the ballistician some insight as to where the ball will fall based on the previous behavior of the wheel.

Again, this is all theoretical to me as I have never seen anyone prove to be that they have this ability to a sufficient-enough degree to overcome the high House Edge of Roulette. I’m not saying they don’t, there are people who say, “You can’t beat slot machines,” and that’s demonstrably untrue in some cases. I’m just saying that I’ve never witnessed Visual Ballistics pulled off in person or in any video consisting of a live casino environment.

Although, we do know that there have been biased wheels in the past such that they favor some numbers over others. This can come down to irregularities on either the wheel itself, or potentially, in the pockets such that the bounce of the ball can be affected.

Why are we talking about Roulette? I’m sure you’re wondering that.

Roulette is up for discussion because a man named Michael Larson once took those very same concepts that would be applied to visual ballistics and used them to beat a game show.

Start with the Assumption that it’s NOT Random

Yes. A game show.

I envy those of you old enough to remember the original run of my favorite game show of all time, Press Your Luck, as I would be relegated to reruns on the USA Network as a child. Fortunately, given the existence of YouTube, (and a very liberal current owner of the trademark or copyright, whichever one it is) I am able to enjoy reruns of the show anytime I like. Back then, as an elementary school kid, Press Your Luck reruns were the only time I’d find myself inside during Summers and had me praying for snow days during the Winter.

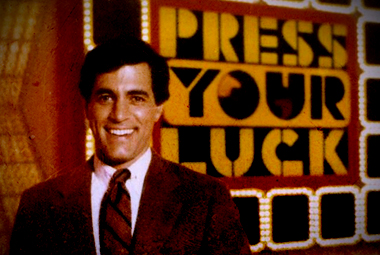

For those of you unfamiliar, Press Your Luck followed a very simple and formulaic modus operandi. The game would start with introductions of all of the players, as well as my favorite game show host of all time, Peter Tomarken, and we would usually learn of their occupations and where they were from.

After the formalities were concluded, there would be a first round of questions by which players could earn, “Spins,” on the board that would be used to collect cash, prizes and the occasional unfortunate, “Whammy.” A player could theoretically play until physically unable to continue, and rack up unbelievable sums of money, were it not for that damned Whammy.

The Whammy wasn’t all bad, though, at least not for the viewer. They would usually crash a propeller plane, roller skate into a tree or have some other misfortune befall them before absconding with the player’s cash, so there is some justice in the world. Nevertheless, the sound of landing on the Whammy, which I have tried to vocally duplicate countless times to absolutely zero avail, left absolutely no humor for most players regardless of how the Whammy would be physically harmed.

The second round would consist of another series of questions in order to obtain spins, and then the players would play on the same board, though with increased prize values. The biggest cash prize on the board was $5,000 + Spin, which could be accessed by hitting it directly, or by hitting the square that says, “Big Bucks,” while it was also showing on the board.

While the game seems very rudimentary and simple, there was some degree of strategy involved even for players not named, “Michael Larson.” The strategy would mostly involve how the player would play the second round, because there would be spins in both the, “Earned,” column as well as the, “Passed,” column.

In the event that a player had some number of spins left, those spins could then be passed and would automatically either go to the person in first place, or alternatively, would go to the person in second place if the player doing the passing was in first place already.

The goal of passing spins was twofold:

1.) To avoid hitting a Whammy yourself.

2.) To hopefully cause the other player to hit a Whammy.

Of course, Press Your Luck would not be a very good game if Whammies were hit more often than not, because then even a winning player would not leave with very much. In fact, even with the rules and board such as they were, there have been multiple three way ties in the show’s history that would have all players finish with $0.

One situational point that should be mentioned is that, in the event that a player collected four Whammies, that player would immediately be out of the game and all remaining spins would be nullified. Given the relatively low probability of hitting the Whammy, that was one of the few situations in which it made unarguable sense to pass one’s spins, especially if one also happened to lead by a seemingly insurmountable amount of dollars. For example, given that $5,000 + Spin is the biggest possible cash take in the second round, a player leading by $8,000, but with three Whammies, might do well to go ahead and pass a single spin to another player hoping for that player not to amass $8,000. The game would end when that player either hit a Whammy, or some amount that did not reward the player an additional spin.

One aspect of the game that might be a bit of a point of amusement for Pass Line players on Craps is the fact that the probability of hitting a Whammy on a single spin was 1 out of 6. The same Odds as rolling a seven after a point has been established and, “Sevening Out.”

Maybe Bill Carruthers, the creator of the show, was a Craps fan. I researched the matter briefly, but couldn’t find anything definitive.

For those who think betting systems are bound to work eventually, or have any mathematical value against the House Edge whatsoever, I strongly recommend watching a few episodes of Press Your Luck! They will quickly learn that the Whammy, much like that seven, is bound to turn up sooner or later, often a few times in a row.

It’s hard to say what the odds would be, if truly random, but a player could theoretically (non-zero probability) play for as many as 100 spins on the, “Big Board,” or more, by hitting amounts with an extra spin attached and avoiding Whammies.

Back to passing spins, occasionally a player would find himself with spins in the, “Passed,” column that had to be taken, with one exception. If the player had spins in the, “Passed,” column, and that player were to hit a Whammy, then the player would have any remaining spins move from the, “Passed,” column to the, “Earned,” column. At that point, the player could, “Press Your Luck,” or could choose to pass those spins.

It was a great structure as it enabled there to be some level of drama and uncertainty even at the end of many shows when a player who was in first or second hit a Whammy off of Passed spins. At that point, if the deficit seemed insurmountable, it would not be erroneous to either try to hit some amount on the big board (so the player wins something) and then pass the remaining spins hoping for the other player to Whammy, or to pass them immediately in the hopes of a three-way tie with $0.

Discretion had to be exercised in order to do that, though. If the player hit a Whammy and had $0, that player would certainly need to try to get into second place before passing any spins, otherwise, the player would not have the opportunity to spin again. That was nullified, of course, if the third player also had $0. The player could then pass a spin, or multiple spins, hoping for a three-way tie.

Many players did not know the probability of the Whammy ahead of time, and even if they did, probably could not mentally come up with an optimal situational strategy for either passing, or taking, the spins. That’s one of the fascinating aspects of the show to me, seeing how people differ in their natural behavior in given situations. For example, I’ve seen a few instances in which a player, down only by a couple thousand, would pass one remaining spin (though rare) hoping for the other person to hit a Whammy. The player doing the passing would have had a much better probability of winning just by taking the spin.

The best example that I can think of, without going back and watching a ton of episodes, came from the pilot for Whammy: The All-New Press Your Luck, which also starred Peter Tomarken for the pilot episode. If you start this video at about the 16:30 mark.

You will see Michelle, with $13,790, passes her final spin to Barry, who has $13,191.

This is an awful decision because almost anything on the board, with exception to a Whammy, would result in Barry winning the game. Assuming the probability of the Whammy was roughly the same, combined with the rough probability of hitting something else (plus a spin) and then hitting a Whammy, Michelle would have been way better off just to take her final spin.

Freeze framing the game, the only spot I notice (aside from a Whammy) that would cause Barry to immediately lose the game was the lone $500 square without an additional spin. To be quite clear, Barry should have, by all probability, had the win handed to him by Michelle.

Sometimes that one in six hits, though, as Barry would find out when he hit the Whammy causing Michelle to win. He probably wasn’t too disappointed, though, my understanding is that they use actors who are not playing for real money in pilot episodes of game shows. They’re basically just, “Pitches,” so to speak.

The decisions made by players on the original Press Your Luck would range from equally head-scratching, to brilliant (but perhaps accidentally so) to questionable. I’ve enjoyed much time analyzing whether or not I think the player made the right decision given certain scenarios, but it’s really complicated (in some cases) to make an absolute determination. Believe it or not, it often results in a fun mathematical experiment.

The reason why is because the exact probabilities of any given square were known. While the show would claim that the Big Board was random, the truth of the matter is that it was anything but. In fact, in the early days of the show, there were only 54 possible squares, with nine of them (there’s your one in six) being Whammies.

Specific prizes on the board would change and would often have unknown value until the value was announced. (That happened if a player hit it, or if it was some sort of special prize that was announced before the beginning of the second round) Those prizes, if hit, would then be removed and usually replaced with a cash square or different prize.

When it comes to those decisions that require mathematical breakdowns, the changing cash value of the prizes made it difficult because they were both inconsistent and non-intuitive. For instance, there would be motorcycles worth less than a few grand whereas there would be trips worth much more. Some of the trip amounts seemed exorbitant even by today’s numbers!

The Strategy is Irrelevant

Michael Larson didn’t have to worry about any of that, and nor did he have to worry too much about strategy.

The pattern-recognition receptors in Larson’s brain must have been dialed up to eleven, because as an avid fan of the show, he quickly recognized that the board behaved in identifiable patterns. Where money is involved, that which is identifiable is exploitable, and Larson did just that.

Quite simply, the original Press Your Luck board consisted of the aforementioned 54 squares, but more importantly, those squares also existed on three separate screens. Only three separate screens. In other words, every single prize available would appear in the same spot (that was by design) on one in three screens, on average.

More importantly, the actual cursor (for lack of a better word) that would freeze when a player hit the button, thereby awarding the prize or Whammy, was also not random. In fact, there were a total of five looping patterns that could be switched, but never changed, by way of the producers hitting one switch or another.

After exhaustive study, Larson would identify not just the three possibilities, per square, but also the exploit that was available by way of the five looping patterns. Each of those five patterns contained within it multiple possibilities that would result in the player receiving a cash prize as well as another spin, but that by itself would not have necessarily been enough.

The reason why is that muscle memory comes into play to some extent, which is to say hitting the button at the right time.

Starting top left and going clockwise, with top left being referred to as, “Square One,” Larson would identify that both squares four and eight ALWAYS contained a cash prize and another spin.

The process of memorizing the five looping patterns as well as their correspondence to those two squares, or when they would hit Big Bucks, (another cash + spin opportunity as, “Big Bucks,” automatically went to the best square, square four) was an exhaustive one. Larson would spend hours with multiple TV’s, VCR’s and recordings of previous shows using his remote controls to practice stopping the board at the right time.

For those of you thinking he didn’t put the hours in, much to his then-fiance’s exhaustion and disgust, he would labor at the task obsessively, for as many as eighteen hours a day, until he identified the perfect combination of the loop, squares and patterns.

Even for Larson the task was incredibly arduous, despite him spending so many hours every day on it for over half of a year. It was made somewhat easier by his realization that many parts of the loop could be ignored completely. Regardless of which of the five loops was going at a given time, there was always a point in time that he could isolate one particular square and look for one particular pattern. He would simply wait for a combination of two squares to light up, one after the other, and then he would not what loop he was on and where he was in the loop.

You can find the episode on Youtube, and one thing that you will notice is his intense concentration, eyes darting around furtively, as he tried to appear to be playing, “Naturally,” while simultaneously looking for the combination of squares that acted as a, “Tell,” for what loop he was on and where he was at in the loop.

It also becomes evident what he was doing when you notice that sometimes he would hit the button relatively quickly, while at other times, it would seem like several seconds before he hit the button. The simple fact of the matter was that it would be too much to memorize the entirety of each individual loop, which is what he started out trying to do, before realizing that he could isolate specific parts of the loop, chronologically close to the target square, and go from there.

All of the strategy that would otherwise be part of the game, the spin passing, the element of, “Luck,” (which truly didn’t exist!) was gone. The only thing that remained was getting the spins.

Oh, and getting on the show, I guess that would help, too.

Larson basically invested all of the money that he had on him into getting to Los Angeles, to the Press Your Luck studios and walked in claiming to be a huge fan of the show who wanted nothing more than to appear on the program.

Imagine his nervousness on that long bus ride, which would have been thirty-two hours if the bus could go nonstop and without any switches, (obviously not the case) with the burden weighing on his mind that all of the work he put into recognizing and analyzing the patterns had been for nothing. What if he were to walk into Television Studios only to find that they did not want him for the show?

All of the work and dedication he had put into his master plan would be for nothing. Not only did Michael Larson gamble using his last money to get that bus ticket, but he had also gambled with literal months worth of time. He had basically lived the last several months as a hermit, studying his TV screens almost unceasingly, clicking the pause button on the remote so many times that he probably wore out multiple units and it could have all been for nothing.

In fact, it almost was.

Bobby Edwards was the, “Contestant Supervisor,” for the program. Essentially, his job was to host the two daily periods of auditions for as many as fifty players per audition, and to decide who he would or would not like to have on the show.

Not to disparage the deceased, but Michael Larson was neither an unattractive man, nor was he a knock-out, by anyone’s standards. Giving his story of being a currently unemployed ice cream truck driver from Ohio, he walked into the studios and Edwards smelled a rat, though it was a rat he couldn’t quite put his finger on. Either way, Larson was an affable enough looking character, and despite being slightly overweight and middle-aged, didn’t look terrible on TV.

The creator, Bill Carruthers, was also the Executive Producer of the show. By some means, Larson managed to get an audience with him and he suggested to Edwards that Larson would be an okay choice for the program. The story of an out-of-state guy unemployed, poor and down on his luck getting a chance of earning considerable money, he felt, would make for compelling TV.

Very often, the people who would appear on the program were professionals, and sometimes even actors, who had enjoyed varying degrees of success in life. Subdued, attractive and often immaculately dressed, they made for a good visual, but a not terribly compelling story. Where’s the fun in someone well-to-do already winning money that would go straight into discretionary income, or maybe a bathroom remodel, something like that?

In Larson, Carruthers saw a potential contestant for whom the amount of money to be won (which, at the time, had a limit per contestant of $25,000) would actually be life-changing. He expected Larson to exude tremendous emotion while playing the game, celebrating every good square, loudly bemoaning every Whammy. Hell, maybe he’d even shed a tear. That’d be compelling.

The rule on the $25,000 wasn’t strictly $25,000, of course. The way it worked was that any winning contestant would return on the following episode, provided the total winnings were under $25,000. Once in excess of the $25,000, of if more than $25,000 was earned in a single episode, the contestant would not be eligible to return.

In fact, as of that time, no television game show contestant in history had ever earned as much as $40,000, so the arbitrary stop rule of $25,000 was not even needed.

Against the protests of Edwards who insisted, “Something just doesn’t seem right,” Larson would appear on the fifth taping of the day.

Larson would appear on the show in a shirt and jacket that he had purchased for under a dollar at a nearby thrift store. His competition would consist of dental assistant, Janie Litras as well as Baptist Minister, Ed Long. Ed Long found himself perplexed, having befriended Larson whilst they were waiting to play, when Larson deadpanned, “I hope we don’t have to go against each other.” Fortunately for Long, he would be appearing as the returning champion on that fifth taping, having been the winner on the fourth. Janie Litras, however, would not be so fortunate. In that game of Press Your Luck, Larson would be playing the part of the House...and the House always wins.

The dice were loaded. Larson would not hit any Whammies because he could not hit any Whammies, he had worked long and hard to make that a virtual impossibility. The question for Larson wasn’t going to be, “If?”, it was merely a matter of, “How much?”

Or, was it?

Let’s not forget that Larson still had to earn the spins, and there wasn’t anything that he could game to effectuate that. In a fairly common blunder on the show, he would buzz in prior to the question being finished (the first to answer without multiple choice gets three spins, all other correct answers get one) and answer that Franklin D. Roosevelt was in his pocket on a $50 bill. The part of the question he didn’t hear would end, “...on what American coin?”

One question and zero spins later, Larson was probably cursing himself for his mistake and the possibility that he could conceivably finish the game with zero spins, rendering everything he had done before that moot, must have dawned on him. He sat mutely and simply mimed the answers of those who would answer before him, thereby garnering three spins to the ten and seven for the two other players.

No problem, right? The guy only needs one, doesn’t he?

As it turns out, not so much. If he had only one spin to his name, it may well have been a Whammy, because much to his chagrin and confusion, that’s what his first spin was! It may have been a matter of being overcome by nerves, or it may have been a slight difference in the timing between the stop button as opposed to the pause button of a VCR remote, but he was off. Maybe this wouldn’t be so easy.

Larson would collect himself and hit square four for $1,250 a pop on each of his next two spins. While that result would not contain an additional spin, square four was his target square, whenever possible, and he needed to practice hitting it on cue. Hitting that result after the early Whammy almost certainly restored his confidence, though he would finish the round in third place with no guarantees of ever spinning again. It was on to the second round of questions.

Larson would experience no such early errors in the second round, being the first to answer without multiple choice on two occasions, and one with, amassing a total of seven spins.

He hit his preferred square, square four, with each of his first two spins. Over the next several spins, he would experience four results that were not in either of his target squares, four or eight. In the meantime, the producers finally got a stronger whiff of the rat that Edwards had smelled earlier.

He knew.

He was celebrating too early, according to the producers. In other words, a, “Normal,” contestant would not have been able to analyze the result of the spin as quickly as he did. What happened was that he was actually celebrating the fact that he knew he had hit the button at the right time, which resulted in what clearly appeared to be a preemptive celebration.

He also had a clear expression of bewilderment, prior to celebrating, anytime that he would hit one of the other squares. Normally, a contestant would see the prize and celebrate, but Larson was trying to figure out what went wrong.

These problems were temporary and Larson would go on to nail one of the two desired squares with thirty-one consecutive spins. Host Peter Tomarken was literally pleading with him to quit, at the direction of the producers, but with sweat pouring out of his face and the realization of what he had pulled off setting in, Larson finally succumbed to exhaustion and passed his spins.

He would pass his spins only after he had earned over $100,000 in cash and prizes, perhaps a preplanned stopping point.

The game wasn’t over, though, as Litras would go on to pass a few spins back to Larson, but the man had a contingency plan. In this case, a couple of backup target squares that did not contain an extra spin, but also would not contain a Whammy.

After a meeting scrutinizing his methods the following day, CBS Executives determined that Larson did not violate any rules of the show, and therefore, was entitled to the money and prizes.

His brother James would say of Larson that he had a habit of trying to make money outside of the realm of traditional employment, often to his own detriment. In fact, with most of that money after taxes and a determination to become more responsible, Larson would look into the possibility of real estate investments.

Unfortunately, a not-so-solid advantage play, of sorts, would be brought to his attention. There was a radio contest by which a random number would be read every day, and if a participant were to have a $1 bill matching that number, he or she would win $30,000. Larson would routinely withdraw and deposit $50,000, all in singles, in the bank, but would eventually grow tired of doing that. They were then stolen from his house while at a Christmas party.

After that, he would get into the Ponzi Scheme game and effectively become a fugitive.

Conclusion

If there’s one person on Earth that I think would have been an amazing advantage player in casinos, that person is Michael Larson. There has perhaps never been a person willing to work as hard to, “Not work,” but when you look at the hourly on his pursuits:

Let’s pretend for a second that Larson went to work for 18 hours a day (as reported) analyzing the game with his VCR’s and televisions. We also know he did it for six months, but we’ll pretend he averaged 25 days a month, taking a few off:

110237/18/150 = $40.83

He made $40.83 per hour worked, not including the investment to get to L.A., the time traveled in doing so or his time actually spent on the show. While that is certainly a more than respectable hourly earn, one must also consider that he was out of the labor force during that time and had also invested the time on a one-time affair. Beyond that, there was absolutely no guarantee of earnings because he had no way of knowing, at the time that he left, that he would be chosen to be on the show in the first place.

Either way, the skills that are required to do what he did, as well as an insatiable desire to make money by non-traditional means, on one’s own terms, are exactly the sorts of things that an AP needs. In fact, when it comes to certain opportunities on different slot titles, Larson probably would be able to identify and figure out how to exploit certain machines within seconds of beginning to observe them.

More importantly, the silver tongue that led Carruthers to overruling Edwards and putting Larson on the show could also serve him well with hosts as well as other players. He’d managed to gain a reported three million dollars in his Ponzi schemes, anyway, so it’s pretty clear that he could be convincing when he wanted to be.

While his brother might accuse him of having a poor work ethic, one can be sure that the exact opposite was likely true, it just had to be on his terms. Anyone who could spend countless hours watching recordings of the same game show, in a dimly lit room, hitting the pause button on a remote and memorizing patterns would certainly have the tenacity to sit down at an advantageous slot machine, perhaps some sort of long-shot progressive, and play it until it hits. There are no words to adequately express the singular dedication that was required to pull off what he did, even though it sounds pretty easy on paper.

Beyond that, anyone who could memorize those sorts of patterns and situational play could easily memorize optimal strategy for several video poker games, one would think. That would enable him not just to play machines that are advantageous, “Right off the top,” for long hours, but also to do so optimally as well as figuring out advantages on drawings or offers, as appropriate.

I don’t really know whether or not Michael Larson gambled in casinos, I’ve researched the question fairly thoroughly and have no real answers on it. He may well have just figured, “The House always wins,” and lost interest before ever really exploring them. One has to assume that he didn’t have much of an interest, anyway, because I am firmly convinced he would have went on to become one of the best advantage players out there.

Comments

I used to love PYL growing up as well. It was one of the few bright spots in having to stay home sick from school! I remember watching the episode that featured Larson. Looking back, I have concluded that it was indeed a day I was sick because I clearly remember the first episode. (They actually broke this particular game into two episodes due to time constraints.) But I don't remember seeing the 2nd half until the show was into syndication. Obviously, I was feeling better and back in school the next day!

I never really thought of it back then, but I would say that PYL has the most involved strategy of any game show I've seen (assuming random play). And, as you mentioned, contestants would often make really bad decisions. I still like watching the random episode on Buzzr. Speaking of which, a year or so ago, they (Buzzr) ran a 1-hour documentary on Larson and PYL. If it's not on Youtube, I'm sure they will run it again at some point in the future.

I agree, he would have made one hell of an AP!

Joeman,

Absolutely! Were you a, 'Wonder Years,' guy, too? That was probably another home from school sick standby for me!

Yes, Larson ran so long that they had no choice but to chop the episode into two parts, with the second part opening with a monologue by Tomarken discussing the events of the first episode. I think it was a Friday/Monday thing, actually, but could be wrong.

PYL was definitely strategy-heavy, maybe the heaviest up to that time, but I might contend that shows such as, 'The Weakest Link,' may come close if not beat PYL. Final Jeopardy is also fairly strategy-heavy, too...Daily Doubles also. The long-form documentary I've seen is "Big Bucks: The Press Your Luck Scandal," which would also include a game between Larson's brother, Jamie Litras and Ed Long in the, "Whammy: The All-New Press Your Luck," format.

Good article! I was familiar with this story and find it fascinating. As a Vegas resident for 17 years, I know plenty like Larson. People who will partake in the advantage play de jour for 80 hours a week to avoid working a real job for 40.

If i ever get a web site going about game shows, I hope you'll join me.

Wizard,

Thanks for the compliment! I'll definitely be all over that site with you when you get it going!