Poll

| 25 votes (49.01%) | ||

| 16 votes (31.37%) | ||

| 7 votes (13.72%) | ||

| 4 votes (7.84%) | ||

| 12 votes (23.52%) | ||

| 3 votes (5.88%) | ||

| 6 votes (11.76%) | ||

| 5 votes (9.8%) | ||

| 12 votes (23.52%) | ||

| 10 votes (19.6%) |

51 members have voted

Quote: Gialmere...what color would your Lamborghini be?

link to original post

I grew up next door to someone who owned one. It kept breaking down.

Actually, I would take the other option - because this is a genie we are talking about, and if I did take the car, my choice would be the lead story on pretty much every 24/7 news source immediately, and the front page of every newspaper in the country the next day.

Then again, for all I know, the genie would "end world hunger" by making half of the population disappear - the female half. "Hey, at least you won't have to worry about the next generation starving!"

On the Food Networkís latest game show, Cranberries or Bust, you have a choice between two doors: A and B. One door has a lifetime supply of cranberry sauce behind it, while the other door has absolutely nothing behind it. And boy, do you love cranberry sauce.

Of course, thereís a twist. The host presents you with a coin with two sides, marked A and B, which correspond to each door. The host tells you that the coin is weighted in favor of the cranberry door ó without telling you which door that is ó and that doorís letter will turn up 60 percent of the time. For example, if the sauce is behind door A, then the coin will turn up A 60 percent of the time and B the remaining 40 percent of the time.

You can flip the coin twice, after which you must make your selection. Assuming you optimize your strategy, what are your chances of choosing the door with the cranberry sauce?

Extra credit: Instead of two flips, what if you are allowed three or four flips? Now what are your chances of choosing the door with the cranberry sauce?

I would flip the coin once and note the result, and then flip it again. If I get the same result on both flips, I assume that that side is the cranberry door. If I get differing results for the two flips, I will pick the door I got on the first flip,

Let's say that A is 0.60 and B is 0.4.

The frequency of outcomes is:

AA: 0.36

AB: 0.24

BA: 0.24

BB: 0.16

So, when the result is the same for both flips, I will be correct with a frequency of 36/52 or about 69.2307692% When i get different outcomes for the two flips, I claim I should be correct 60% of the time using my strategy.

My total chance of being correct is 0.52*(0.36/0.52)+0.48*0.6 = 0.648 or 64.8%

For the 2-flip problem, I'll go with "the obvious answer": use just the first flip. You have a 60% chance of success.

I am half-expecting the "QI Klaxon" at this point, for those of you who know what that means.

Quote: gordonm888Cranberries or bust

I would flip the coin once and note the result, and then flip it again. If I get the same result on both flips, I assume that that side is the cranberry door. If I get differing results for the two flips, I will pick the door I got on the first flip,

Let's say that A is 0.60 and B is 0.4.

The frequency of outcomes is:

AA: 0.36

AB: 0.24

BA: 0.24

BB: 0.16

So, when the result is the same for both flips, I will be correct with a frequency of 36/52 or about 69.2307692% When i get different outcomes for the two flips, I claim I should be correct 60% of the time using my strategy.

My total chance of being correct is 0.52*.692307692+0.48*0.6 = 0.648 or 64.8%

link to original post

I donít follow:

ETA: isnít your strategy functionally equivalent to flipping the coin once and going with that door? It sounds like you will always pick the first coin flip door no matter what the second coin flip is. So you should be right 60% of the time with your strategy.

I get 60%. I show this to be true for any weighting of the correct side of the coin.

1 flip = 60.000%

2 flip = 60.000%

3 flip = 64.800%

4 flip = 64.800%

5 flip = 68.256%

With three flips you have more information if the first two are both the same. If so, there's a 16% chance of it being wrong and 36% chance of being correct, so you stick.

The remaining 48%, one of each, at this stage there's only a 50% chance of the second flip being correct (as it's equally likely you got XY or YX), so you flip again. The third flip has a 60% of being correct and so adds 60%*48%=28.8% chance of winning. Total chance = 36% + 28.8% = 66.8%.

With four flips use the above logic but if you need a third flip then this is equivalent to starting with two flips - so it doesn't add any help having a fourth flip available. Also say you're first two flips were the same; if you continued the only time it would give a better result would be it was X X Y Y where X was wrong (5.76%), this is offset by creating the loss for YYXX. Other cases XXX XXYX YYY YYXY leave you on the same decision. Thus it's just as easy to use the 3-flip logic.

With 5-flips it gets to 68.256% if you always flip 3-times (slightly better 67.104% than stopping if the first two are the same) Basically if you see the third occurrence of the same side you stand. I wonder if this is the best strategy for large numbers, wait for any side to exceed half the total number of flips available.

With an even number you would try and pick the majority so will always stick on 3 out of 4. What is interesting if if the first two are the same then you are better off to stick since the only occasion that can change your mind is if the rest are opposite (in which case it's 50/50, so you might as well pick the first two that came out). So in practice you might as well stick as soon as you see 2 the same.

Thus it doesn't matter if you finish all the flips or if you stop flipping once you see the current leader cannot be beaten. This means you can always stop flipping and make that flip the side you are choosing.

Quote: Wizard

1 flip = 60.000%

2 flip = 60.000%

3 flip = 64.800%

4 flip = 64.800%

5 flip = 68.256%

link to original post

Correct!!

Surely, you had better odds of winning with two flips instead of one. Right?

Wrong. To see why that was, solver Rebecca Harbison looked closer at the possible results of the two flips. Instead of A and B, letís relabel the coin C (for ďCranberry sauce is behind this doorĒ) and D (for ďDangit, no cranberry sauce behind this doorĒ). As stated by the problem, the coin had a 60 percent chance of landing on C and a 40 percent chance of landing on D.

With two flips, there were four possible outcomes:

The first flip was C and the second flip was also C, which occurred with probability (0.6)(0.6), or 0.36.

The first flip was C and the second flip was D, which occurred with probability (0.6)(0.4), or 0.24.

The first flip was D and the second flip was C, which occurred with probability (0.4)(0.6), or 0.24.

The first flip was D and the second flip was D, which occurred with probability (0.4)(0.4), or 0.16.

Putting these together, there was a 48 percent chance that the two flips were different. When this happened, you had absolutely no information how the coin was weighted, since the coin came up either side an equal number of times. In other words, you had to guess, which meant youíd be right half the time.

The other 52 percent of the time the two flips were the same. The majority of the time (i.e., with probability 36/52, or 9/13) that meant both flips were C. So when the two flips were the same, your best move was to guess the door both flips corresponded to.

So then what were your chances of winning the cranberry sauce? Well, 48 percent of the time you had a one-half chance of winning, while the other 52 percent of the time you had a 9/13 chance of winning. Numerically, these combined to (12/25)(1/2) + (13/25)(9/13), which simplified to 6/25 + 9/25, or 15/25 ó in other words, 60 percent.

Shockingly (to me, at least), that second flip didnít improve your chances one bit. You might as well have simply flipped the coin once and chosen the resulting door.

For extra credit, you looked at what happened when you were allowed three or four flips, instead of just two. For three flips, the optimal strategy was to choose whichever door was indicated by a majority of the flips. All three flips came up C with probability (0.6)3, or 0.216. Meanwhile, the probability of two Cs and one D was 3(0.6)2(0.4), or 0.432. Adding these together meant youíd win the cranberry sauce 64.8 percent of the time ó an improvement over your chances with just one or two flips.

But just as two flips were no better than one, four flips were no better than three. That fourth flip either confirmed your decision based on the first three flips, or changed things so that now there were two flips for one door and two flips for another (opening up twice as many possibilities, and forcing you to take a random guess).

Solvers Jake Gacuan and Emily Boyajian both found a general formula for your chances of winning the cranberry sauce as a function of the number of flips N. Sure enough, having an even number of flips was no better than having the preceding odd number of flips. And as N increased, your chances of choosing the correct door approached 100 percent.

-------------------------------------------------------------

How many different ways can you read WAS IT A CAT I SAW, i.e., WASITACATISAW, moving in single steps up, down, left or right?

:strip_icc()/pic6564093.png)

---------------------------------------------------------

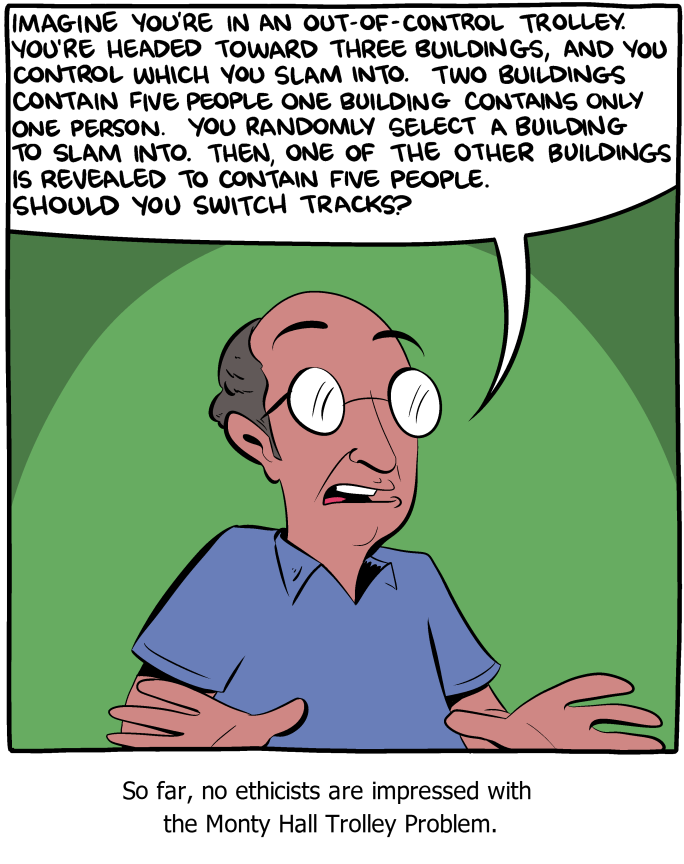

The Monty Hall problem is a classic case of conditional probability. In the original problem, there are three doors, two of which have goats behind them, while the third has a prize. You pick one of the doors, and then Monty (who knows in advance which door has the prize) will always open another door, revealing a goat behind it. Itís then up to you to choose whether to stay with your initial guess or to switch to the remaining door. Your best bet is to switch doors, in which case you will win the prize two-thirds of the time.

Now suppose Monty changes the rules. First, he will randomly pick a number of goats to put behind the doors: zero, one, two or three, each with a 25 percent chance. After the number of goats is chosen, they are assigned to the doors at random, and each door has at most one goat. Any doors that donít have a goat behind them have an identical prize behind them.

At this point, you choose a door. If Monty is able to open another door, revealing a goat, he will do so. But if no other doors have goats behind them, he will tell you that is the case.

It just so happens that when you play, Monty is able to open another door, revealing a goat behind it.

Should you stay with your original selection or switch? And what are your chances of winning the prize?

Letís assume you picked door #1 to start.

The fact that Monty could open a door means you arenít in a world with zero goats or a world with one goat that is behind the door #1. That eliminated 33% of the options (25% zero goat and 1/3*25% one goat in door #1).

If you stick with your door, you win 37.5% of the time (if thereís one goat (2/3*25%) or if thereís two goats but behind doors #2 and 3 (1/3*25%). So thatís 25% winners dividing by total of 66.67% of possible worlds = 37.5%.

If you switch you win 50% of the time. (Win all one goat options and two goat options where one goat is behind door #1. That adds to 4/3*25% = 33.33% of the total 66.67%).

As will be seen their probabilities given the info now known aren't identical!

(a) There's only one goat, it doesn't matter whether you switch or not as the others contain a prize. Chance of winning 1 (or 3/3).

(b) There are two goats, as in regular Monty, you should switch so your chances are 2/3.

(c) There are three goats, therefore you have no chance as there's one behind every door, your chances are 0/3.

Thus regardless of the chances of each you are better off (or identical) by switching.

The initial chances of (a) was 1/3, but one of those has a goat in the box you chose, so the conditional chance is 2/8.

(b) and (c) have chances of 3/8.

Thus the total chance is (2/8*3/3+3/8*2/3+3/8*0/3) = (6+6+0)/24 = 50%.

(Sticking is (6+3+0)/24 = 3/8.)

Since a goat was revealed, then either 1, 2, or 3 doors have goats.

1/3 of the time, one door has a goat; before the reveal, you have a 2/3 chance of winning.

1/3 of the time, two doors have goats; before the reveal, you have a 1/3 chance of winning.

1/3 of the time, all three doors have goats; you have zero chance of winning.

The overall chance of winning if you do not switch = 1/3 x 2/3 + 1/3 x 1/3 + 1/3 x 0 = 1/3.

The chance of winning if you do switch = 1 - 1/3 = 2/3.

Therefore, you should switch; you have a 2/3 chance of winning the prize.

Quote: ThatDonGuy

Since a goat was revealed, then either 1, 2, or 3 doors have goats.

1/3 of the time, one door has a goat; before the reveal, you have a 2/3 chance of winning.

1/3 of the time, two doors have goats; before the reveal, you have a 1/3 chance of winning.

1/3 of the time, all three doors have goats; you have zero chance of winning.

The overall chance of winning if you do not switch = 1/3 x 2/3 + 1/3 x 1/3 + 1/3 x 0 = 1/3.

The chance of winning if you do switch = 1 - 1/3 = 2/3.

Therefore, you should switch; you have a 2/3 chance of winning the prize.

link to original post

You neglected a piece of information.

Quote: unJonQuote: ThatDonGuy

Since a goat was revealed, then either 1, 2, or 3 doors have goats.

1/3 of the time, one door has a goat; before the reveal, you have a 2/3 chance of winning.

1/3 of the time, two doors have goats; before the reveal, you have a 1/3 chance of winning.

1/3 of the time, all three doors have goats; you have zero chance of winning.

The overall chance of winning if you do not switch = 1/3 x 2/3 + 1/3 x 1/3 + 1/3 x 0 = 1/3.

The chance of winning if you do switch = 1 - 1/3 = 2/3.

Therefore, you should switch; you have a 2/3 chance of winning the prize.

link to original post

You neglected a piece of information.

link to original post

I assume you are thinking that I "forgot" that if only one door has a goat behind it, then the probability of winning is 100% if I keep my door. Doesn't this cause the same problem as the original Monty Hall problem involving, "Well, there's a 50/50 chance whether or not I switch"?

Quote: ThatDonGuyQuote: unJonQuote: ThatDonGuy

Since a goat was revealed, then either 1, 2, or 3 doors have goats.

1/3 of the time, one door has a goat; before the reveal, you have a 2/3 chance of winning.

1/3 of the time, two doors have goats; before the reveal, you have a 1/3 chance of winning.

1/3 of the time, all three doors have goats; you have zero chance of winning.

The overall chance of winning if you do not switch = 1/3 x 2/3 + 1/3 x 1/3 + 1/3 x 0 = 1/3.

The chance of winning if you do switch = 1 - 1/3 = 2/3.

Therefore, you should switch; you have a 2/3 chance of winning the prize.

link to original post

You neglected a piece of information.

link to original post

I assume you are thinking that I "forgot" that if only one door has a goat behind it, then the probability of winning is 100% if I keep my door. Doesn't this cause the same problem as the original Monty Hall problem involving, "Well, there's a 50/50 chance whether or not I switch"?

link to original post

Not that.

Let's just say the other doors have a car.

Pr(original door has a car given goat revealed) = Pr(original door has car and goat revealed)/Pr(goat revealed)

Pr(original door has car and goal revealed) = Pr(0 goats)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(chosen door has car) + Pr(one goat)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(chosen door has car) + Pr(two goats)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(chosen door has car) + Pr(3 goats)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(chosen door has car) =

(1/4)*0*1 + (1/4)*(2/3)*1 + (1/4)*1*(1/3) + (1/4)*1*0 = 2/12 + 1/12 = 3/12 = 1/4.

Pr(goat revealed) = Pr(0 goats)*Pr(goat revealed) + Pr(one goat)*Pr(goat revealed) + Pr(two goats)*Pr(goat revealed)+ Pr(3 goats)*Pr(goat revealed) =

(1/4)*0 + (1/4)*(2/3) + (1/4)*1 + (1/4)*1 = 2/12 + 3/12 + 3/12 = 6/12 = 8/12 = 2/3.

So, Pr(original door has a car given goat revealed)= (1/4) / (2/3) = (1/4)*(3/2) = 3/8.

----

Pr(other door has a car given goat revealed) = Pr(other door has car and goat revealed)/Pr(goat revealed)

Pr(other door has car and goal revealed) = Pr(0 goats)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(other door has car) + Pr(one goat)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(other door has car) + Pr(two goats)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(other door has car) + Pr(3 goats)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(other door has car) =

(1/4)*0*1 + (1/4)*(2/3)*1 + (1/4)*1*(2/3) + (1/4)*1*0 = 2/12 + 2/12 = 4/12 = 1/3.

The probability of a goat revealed is still 2/3.

Thus, the probability the other door has a car, given a goal is revealed is (1/3)/(2/3) = 1/2.

Thus, by staying the player has a 3/8 chance at a car. By switching it is 1/2. Thus, he should switch.

Quote: unJonQuote: ThatDonGuyQuote: unJonQuote: ThatDonGuy

Since a goat was revealed, then either 1, 2, or 3 doors have goats.

1/3 of the time, one door has a goat; before the reveal, you have a 2/3 chance of winning.

1/3 of the time, two doors have goats; before the reveal, you have a 1/3 chance of winning.

1/3 of the time, all three doors have goats; you have zero chance of winning.

The overall chance of winning if you do not switch = 1/3 x 2/3 + 1/3 x 1/3 + 1/3 x 0 = 1/3.

The chance of winning if you do switch = 1 - 1/3 = 2/3.

Therefore, you should switch; you have a 2/3 chance of winning the prize.

link to original post

You neglected a piece of information.

link to original post

I assume you are thinking that I "forgot" that if only one door has a goat behind it, then the probability of winning is 100% if I keep my door. Doesn't this cause the same problem as the original Monty Hall problem involving, "Well, there's a 50/50 chance whether or not I switch"?

link to original post

Not that.There are one goat scenarios that are impossible given our data set. So the conditional probability of 1, 2, and 3 goats is not 1/3, 1/3 and 1/3.

link to original post

Assume you selected door 3

0 goats: impossible

1 goat, behind door 1: 1/12 - win if you keep; win if you switch

1 goat, behind door 2: 1/12 - win if you keep; win if you switch

1 goat, behind door 3: impossible

2 goats, behind doors 1 & 2: 1/12 - win if you keep; lose if you switch

2 goats, behind doors 1 & 3: 1/12 - lose if you keep; win if you switch

2 goats, behind doors 2 & 3: 1/12 - lose if you keep; win if you switch

3 goats: 1/4 - always lose

The sum of the probabilities of the possible events is 2/3

The probability of winning if you keep is (1/12 + 1/12 + 1/12) / (2/3) = 3/8

The probability of winning if you switch is (1/12 + 1/12 + 1/12 + 1/12) / (2/3) = 1/2

The best play is to switch; you have probability 1/2 of winning

Quote: unJonFun problem!

Letís assume you picked door #1 to start.

The fact that Monty could open a door means you arenít in a world with zero goats or a world with one goat that is behind the door #1. That eliminated 33% of the options (25% zero goat and 1/3*25% one goat in door #1).

If you stick with your door, you win 37.5% of the time (if thereís one goat (2/3*25%) or if thereís two goats but behind doors #2 and 3 (1/3*25%). So thatís 25% winners dividing by total of 66.67% of possible worlds = 37.5%.

If you switch you win 50% of the time. (Win all one goat options and two goat options where one goat is behind door #1. That adds to 4/3*25% = 33.33% of the total 66.67%).

link to original post

Quote: charliepatrickThere are three possible initial conditions about the number of goats (since 0 has been ruled out).

As will be seen their probabilities given the info now known aren't identical!

(a) There's only one goat, it doesn't matter whether you switch or not as the others contain a prize. Chance of winning 1 (or 3/3).

(b) There are two goats, as in regular Monty, you should switch so your chances are 2/3.

(c) There are three goats, therefore you have no chance as there's one behind every door, your chances are 0/3.

Thus regardless of the chances of each you are better off (or identical) by switching.

The initial chances of (a) was 1/3, but one of those has a goat in the box you chose, so the conditional chance is 2/8.

(b) and (c) have chances of 3/8.

Thus the total chance is (2/8*3/3+3/8*2/3+3/8*0/3) = (6+6+0)/24 = 50%.

(Sticking is (6+3+0)/24 = 3/8.)

link to original post

Quote: Wizard

Let's just say the other doors have a car.

Pr(original door has a car given goat revealed) = Pr(original door has car and goat revealed)/Pr(goat revealed)

Pr(original door has car and goal revealed) = Pr(0 goats)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(chosen door has car) + Pr(one goat)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(chosen door has car) + Pr(two goats)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(chosen door has car) + Pr(3 goats)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(chosen door has car) =

(1/4)*0*1 + (1/4)*(2/3)*1 + (1/4)*1*(1/3) + (1/4)*1*0 = 2/12 + 1/12 = 3/12 = 1/4.

Pr(goat revealed) = Pr(0 goats)*Pr(goat revealed) + Pr(one goat)*Pr(goat revealed) + Pr(two goats)*Pr(goat revealed)+ Pr(3 goats)*Pr(goat revealed) =

(1/4)*0 + (1/4)*(2/3) + (1/4)*1 + (1/4)*1 = 2/12 + 3/12 + 3/12 = 6/12 = 8/12 = 2/3.

So, Pr(original door has a car given goat revealed)= (1/4) / (2/3) = (1/4)*(3/2) = 3/8.

----

Pr(other door has a car given goat revealed) = Pr(other door has car and goat revealed)/Pr(goat revealed)

Pr(other door has car and goal revealed) = Pr(0 goats)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(other door has car) + Pr(one goat)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(other door has car) + Pr(two goats)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(other door has car) + Pr(3 goats)*Pr(goat revealed)*pr(other door has car) =

(1/4)*0*1 + (1/4)*(2/3)*1 + (1/4)*1*(2/3) + (1/4)*1*0 = 2/12 + 2/12 = 4/12 = 1/3.

The probability of a goat revealed is still 2/3.

Thus, the probability the other door has a car, given a goal is revealed is (1/3)/(2/3) = 1/2.

Thus, by staying the player has a 3/8 chance at a car. By switching it is 1/2. Thus, he should switch.

link to original post

Quote: ThatDonGuy

Assume you selected door 3

0 goats: impossible

1 goat, behind door 1: 1/12 - win if you keep; win if you switch

1 goat, behind door 2: 1/12 - win if you keep; win if you switch

1 goat, behind door 3: impossible

2 goats, behind doors 1 & 2: 1/12 - win if you keep; lose if you switch

2 goats, behind doors 1 & 3: 1/12 - lose if you keep; win if you switch

2 goats, behind doors 2 & 3: 1/12 - lose if you keep; win if you switch

3 goats: 1/4 - always lose

The sum of the probabilities of the possible events is 2/3

The probability of winning if you keep is (1/12 + 1/12 + 1/12) / (2/3) = 3/8

The probability of winning if you switch is (1/12 + 1/12 + 1/12 + 1/12) / (2/3) = 1/2

The best play is to switch; you have probability 1/2 of winning

link to original post

Correct!!

--If there were three goats behind the doors, it didnít matter if you switched or stayed ó youíd always lose.

--If there were two goats behind the doors, then this reverted to the original Monty Hall problem. You had a two-thirds chance of winning the prize if you switched, but just a one-third chance of winning if you stayed.

--If there was one goat behind a door, then Monty just did you a huge favor by showing you which door it was behind. It didnít matter if you switched or stayed ó youíd always win.

--If there were zero goats behind the doors, then youíd always win.

Now you might have thought that each of these cases was equally likely ó but wait just a minute! The fact that Monty was even able to open a door and reveal a goat meant you couldnít have been in the zero-goat scenario. There had to have been at least one goat present.

But that wasnít all. The trickiest part of the problem was around the relative likelihood of the one-goat scenario. If there had been two or three goats, then no matter which door you picked, Monty could always open a different door to reveal a goat. But if there was only one goat, then the one-third of the time you happened to pick that goatís door, Monty wouldnít have been able to open another door to reveal a goat.

All of that meant you were just two-thirds as likely to be in the one-goat scenario as you were to be in the two-goat or three-goat scenarios. In other words, the probability there were three goats was 3/8, the probability there were two goats was also 3/8, and the probability there was one goat was just 2/8.

By combining the probabilities of the different scenarios with your probability of winning the prize within each scenario, you found that, overall, you had a 50 percent chance of winning if you switched, but just a 37.5 percent chance of winning if you stayed.

Solver Geoffrey Lovelace verified these results by running a few hundred thousand computer simulations. And David Zimmerman, meanwhile, extended the problem by looking at the general case where there were N doors (rather than just three), with anywhere from zero to N goats behind those doors. He found that switching always gave you a 50 percent chance of winning the prize, no matter how many doors there were. However, your probability of winning when you stayed with your original door was N/(2(N+1)) ó a value thatís always less than 50 percent.

And so, as with the original Monty Hall problem, your best bet was to switch doors. That is, unless a goat happens to be your idea of a prize.

------------------------------------------------------------

Begin at S (start). Take 1 step in a direction, then two steps, then three steps. Repeat taking 1, 2, and 3 steps until one of the moves lands exactly on F (finish). You may not turn a corner or turn back while making a 2 or 3 step move. Tricky.

What is the minimum number of moves needed to complete the maze?

Quote: TwelveOr21I believe it's 6. Start at S, go right, go down, back up one, go right, and right again to land exactly at F

link to original post

A good stab but incorrect. Note that the final three steps are...

6) right, down, down

...and therefore make an illegal turn during a move.

Quote: Gialmere

BUZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZ!!

Start

1) down x1

2) down x2

3) down x3

4) up x1

5) down x2

6) up x3

7) up x1

8) up x2

9) right x3

10) left x1

11) down x2

12) right x3

13) down x1

14) up x2

15) down x3 = Finish

--------------------------------------------

Firstly the number of moves you can make after a set of three must be even. You can either move 6 (i.e. you don't reverse) or 2 (i.e. forward 1, reverse 2, forward 3). Thus if you think chess, you will always stay on the white squares. The number of moves from "S" to "F" is even and all the circular paths are even, so prior to the final set of moves you will be an even number of squares away from "F", thus you can only end after all third parts.

Working backwards where your previous move must have finished you get

(-1) "E" : Must be two places above "F" (so use the 2-move shuffle).

(-2) You can only get to "E" by moving three spaces from the left hand, thus "D" is on the top row 2nd or 4th across (so you move across, down 2, right 3 to get to "E").

(-3) 2nd across doesn't work, so "C" is in the left hand column (so you move up 1 up 2 right 3 to get to "D"). "C" is four below "S".

(-4) "B" is 2 below "C" (using the 2-move logic)

(-5) As "B" is 6 places below "S" this completes all the moves (i.e. 3*5=15).

On average, how many bets will he win per shooter?

PS You can assume the table is half tourists and half experts, so the poor dice throwing skills of the former are canceled by the superb skills of the latter 😆

50,539,982 / 83,128,959, or about 0.60797

With 24 ways to roll a point and 6 ways to roll a seven, the expectation is to roll a point number 4 times (including repeats) before rolling a seven. Therefore the average number of distinct (not repeated) points rolled must be at least 1.

Quote: Ace2I hope I phrased the question properly

With 24 ways to roll a point and 6 ways to roll a seven, the expectation is to roll a point number 4 times (including repeats) before rolling a seven. Therefore the average number of distinct (not repeated) points rolled must be at least 1.

link to original post

You phrased it correctly; I read it wrong.

The number I got is the number of distinct point numbers made before sevening out. You want the number of distinct place bets won before a seven is rolled.

Questions:

1. Are the bets placed before the shooter's first comeout?

2. Should the shooter make a point, are the bets still active during the next comeout (as opposed to being "off" until another point number is established)?

Assuming the answer to both of these is "yes":

392/165, or about 2.37575758

I agree with that answer. Please show your methodQuote: ThatDonGuyQuote: Ace2I hope I phrased the question properly

With 24 ways to roll a point and 6 ways to roll a seven, the expectation is to roll a point number 4 times (including repeats) before rolling a seven. Therefore the average number of distinct (not repeated) points rolled must be at least 1.

link to original post

You phrased it correctly; I read it wrong.

The number I got is the number of distinct point numbers made before sevening out. You want the number of distinct place bets won before a seven is rolled.

Questions:

1. Are the bets placed before the shooter's first comeout?

2. Should the shooter make a point, are the bets still active during the next comeout (as opposed to being "off" until another point number is established)?

Assuming the answer to both of these is "yes":

392/165, or about 2.37575758

link to original post

Regarding your questions - I donít think either makes a difference. If bets are ever turned off then itís like those rolls never happened

Quote: Ace2

Regarding your questions - I donít think either makes a difference. If bets are ever turned off then itís like those rolls never happened

link to original post

That canít be generally right since the problem ceases when the shooter seven outs. For example, assume your same question, but after placing the bets, the bettor turns them ďoffĒ for three rolls then ďalways on.Ē

Quote: Ace2I agree with that answer. Please show your methodQuote: ThatDonGuyQuote: Ace2I hope I phrased the question properly

With 24 ways to roll a point and 6 ways to roll a seven, the expectation is to roll a point number 4 times (including repeats) before rolling a seven. Therefore the average number of distinct (not repeated) points rolled must be at least 1.

link to original post

You phrased it correctly; I read it wrong.

The number I got is the number of distinct point numbers made before sevening out. You want the number of distinct place bets won before a seven is rolled.

Questions:

1. Are the bets placed before the shooter's first comeout?

2. Should the shooter make a point, are the bets still active during the next comeout (as opposed to being "off" until another point number is established)?

Assuming the answer to both of these is "yes":

392/165, or about 2.37575758

link to original post

Regarding your questions - I donít think either makes a difference. If bets are ever turned off then itís like those rolls never happened

link to original post

My method is a 64-state Markov chain calculated with brute force. I thought about a Poisson-based method, but is there an easy way to calculate, say, all of the results where 4 of the numbers are rolled and then a 7?

1/3 chance of rolling at least one four before a seven (times 1)

+ 2/5 chance of rolling at least one five before a seven (times 1)

+ Ö

The expected number of total point numbers rolled before a seven is 4. This is true whether or not come out rolls are countedQuote: unJonQuote: Ace2

Regarding your questions - I donít think either makes a difference. If bets are ever turned off then itís like those rolls never happened

link to original post

That canít be generally right since the problem ceases when the shooter seven outs. For example, assume your same question, but after placing the bets, the bettor turns them ďoffĒ for three rolls then ďalways on.Ē

link to original post

Quote: Ace2I hope I phrased the question properly

With 24 ways to roll a point and 6 ways to roll a seven, the expectation is to roll a point number 4 times (including repeats) before rolling a seven. Therefore the average number of distinct (not repeated) points rolled must be at least 1.

link to original post

I seem to agree with the masses. Here is my table showing the probability of 0 to 6 points made.

| Total points made | Probability | Expected |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 0.062168 | 0.373009 |

| 5 | 0.101016 | 0.505079 |

| 4 | 0.129245 | 0.516979 |

| 3 | 0.151531 | 0.454594 |

| 2 | 0.170057 | 0.340114 |

| 1 | 0.185983 | 0.185983 |

| 0 | 0.200000 | 0.000000 |

| Total | 1.000000 | 2.375758 |

Quote: Wizard

I seem to agree with the masses. Here is my table showing the probability of 0 to 6 points made.

Total points made Probability Expected 6 0.062168 0.373009 5 0.101016 0.505079 4 0.129245 0.516979 3 0.151531 0.454594 2 0.170057 0.340114 1 0.185983 0.185983 0 0.200000 0.000000 Total 1.000000 2.375758

link to original post

Can someone explain to me what Iím missing? I assume we can drop spoilers at this point.

Wizís table above says the probability of 0 points is 0%. But how is that possible? If the place bets are working from the come out, then thereís a chance of a 7 killing them all before a point number is rolled. Likewise if they are off until a point is established, there is still likewise a probability of a 7 out killing them before another point number rolled.

It seems to me that everyone has an implicit assumption that the six point numbers are made and always on, but rebought if a seven winner is rolled.

Quote: unJonCan someone explain to me what Iím missing? I assume we can drop spoilers at this point.

Wizís table above says the probability of 0 points is 0%. But how is that possible? If the place bets are working from the come out, then thereís a chance of a 7 killing them all before a point number is rolled. Likewise if they are off until a point is established, there is still likewise a probability of a 7 out killing them before another point number rolled.

No, it says the expected value of rolling 0 point numbers is 0, and the probability of doing so is 1/5.

Quote: ThatDonGuyQuote: unJonCan someone explain to me what Iím missing? I assume we can drop spoilers at this point.

Wizís table above says the probability of 0 points is 0%. But how is that possible? If the place bets are working from the come out, then thereís a chance of a 7 killing them all before a point number is rolled. Likewise if they are off until a point is established, there is still likewise a probability of a 7 out killing them before another point number rolled.

No, it says the expected value of rolling 0 point numbers is 0, and the probability of doing so is 1/5.

link to original post

Yup. That makes sense.

A great classical problem and very deep.Quote: Ace2If you randomly pick two numbers (integers) between 1 and 1000, what is the probability they are coprime (largest common divisor is 1) ?

link to original post

Quote: Ace2If you randomly pick two numbers (integers) between 1 and 1000, what is the probability they are coprime (largest common divisor is 1) ?

link to original post

Brute force in Excel using GCD function yields 608,383 / 1,000,000.

Correct. If you randomly pick two numbers between 1 and n, the probability they are coprime is 6 / π^2 =~ 60.79% as n approaches infinity. For n=1000, the probability is within 5 basis points of that at 60.84%.Quote: ChesterDogQuote: Ace2If you randomly pick two numbers (integers) between 1 and 1000, what is the probability they are coprime (largest common divisor is 1) ?

link to original post

Brute force in Excel using GCD function yields 608,383 / 1,000,000.

link to original post

I donít know how to prove this, I only read about it. Interestingly, the reciprocal of 6 / π^2 equals the infinite series 1/1^2 + 1/2^2 + 1/3^2 + 1/4^2ÖI posted a math puzzle using that series a while back

This is another example of how all math seems linked together at some level, often involving e and/or π. Iíve never really thought about primes except when factoring down numbers to simplify a formula. Iíd have never guessed that π (or any formula) would come up in this coprime scenario.

Quote: Ace2Correct. If you randomly pick two numbers between 1 and n, the probability they are coprime is 6 / π^2 =~ 60.79% as n approaches infinity. For n=1000, the probability is within 5 basis points of that at 60.84%.

link to original post

I find things like this fascinating. I almost look at it as evidence of some kind of higher power. Is there a term for this particular limit?

Take a standard deck of cards, and pull out the numbered cards from one suit (the cards 2 through 10). Shuffle them, and then lay them face down in a row. Flip over the first card. Now guess whether the next card in the row is bigger or smaller. If youíre right, keep going.

If you play this game optimally, whatís the probability that you can get to the end without making any mistakes?

Extra credit: What if there were more cards ó 2 through 20, or 2 through 100? How do your chances of getting to the end change?

The probability for 9 cards is 0.5^4=6.25%.

The probability for 21 cards is 0.5^10=0.098%

and a ~66.52% chance of getting to the 3rd card (if you made it to the 2nd card)

for a combined total of ~51.74% of making it to the 3rd card.

Is this correct so far?

Note: At my current "math level " I am not going to go past this even if I am correct so far, because it would take me a real long time to get to the "4th", "5th" and "nth" card average values.